STAYS, A Brief History

…or, How 17th Century Women got their shape

including instructions for how to make them

Please feel free to copy this article freely as long you bear in mind that the author reserves all reproduction and other rights to this article.

If you want to reproduce this for commercial gain please contact us and I’m sure we can arrive at a mutually agreeable deal.

CONTENTS:

History

|

The soft flowing lines of the mediaeval period followed the natural female form. By the start of the 15th century this was changing, waists became high and small – an extra band of stiff material may have helped create this shape. |

| By the mid 15th century fashion had reached its peak of tall, thin lines and the pendulum of style swung to a new broad, straight silhouette and a more rigid, structured form. Italy is usually credited with the invention of the ‘busc’, the first artificial support to the upper body, whilst from Spain came the farthingale, which pushed the skirt into a conical shape. Catherine of Aragon is blamed for bringing both to England.In order to keep the bodice straight and tight a heavy underbodice was now worn, called ‘pair of bodys’. By the mid 16th century this was strengthened and stiffened by whalebones at the sides and back, fastened at the centre of either the front or back, depending on whether boning or a busk was used at the front. |  |

Although James 1 and his wife Anne of Denmark continued Elizabeth’s extravagance of dress the farthingale gradually disappeared, affecting the bodice, which became much shorter. The ‘pair of bodys’ were now known as ‘a pair of stays’ or ‘stays’ and followed the fashionable waistline but kept the long centre front stomacher as seen in contemporary portraits.

|

A short bodice, with tabs, appeared in the 1630’s and was worn throughout the middle of 17th century by the middle and lower classes, long after the fashionable Miss had gone on to other styles. It was either boned or worn over a separate pair of stays. |

| For the ultra fashionable a softer, more rounded silhouette was appearing by the late 1630’s. Stiff patterned brocades and velvets were giving way to plain silks which folded and draped to great effect. The silhouette grew longer and straighter. Stays almost disappeared and became incorporated into the bodice itself, which was now mounted onto a stiff whaleboned lining. |  |

The 1640’s waist began to descend again, the bodice still mounted onto the heavily whaleboned, stay-like foundation. Similar boned bodices were also worn on the Continent.

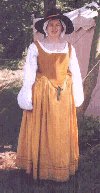

Practical

As there are so few surviving examples of clothes from our period, without the use of an efficient time machine it is difficult to be certain of what was truly worn circa 1645. However having established to my own satisfaction that stiffened bodices were worn, I then had to choose whether to heavily bone all of my bodices or make a pair of stays and only lightly bone any bodices to go over them. Realising that we have a warmish muster occasionally I opted to make a pair of stays which could be worn as a sleeveless bodice on warm days and worn as an underbodice with layers on top for our more usual weather. These I made, lined in cotton and covered in mustard coloured wool.

| Having decided on the fabric, wool and cotton and the pattern the only other bits I needed were the stiffening. I used ridgeline for the whalebone, I have recently discovered ridgeline end-caps which cover the cut ends and stops the sharp bits working their way out of the fabric, I heartily recommend them. The final piece of stiffening was a wooden busk measuring 13 inches (33cms). These were often presented by the woman’s sweetheart or husband and I followed this tradition when my husband bought one as a gift from the Welsh Folk Museum at St Fagans – alas they are no longer available from there. He also drilled the hole at the base to allow it to be laced into the stays. |

|

To make-up the stays I cut an extra pattern in cotton. This I fitted and arranged the ridgeline roughly following Janet Arnold’s drawing – leaving a gap at the front for the busk. As I did not know whether I would be able to wear the stays with the busk I made a pocket of fabric into which it could be inserted and stitched this to the boned interlining. I again checked for fit and made up the wool and cotton bodice and put the interlining in between the two layers before it was completed.

|

Tabs were added afterwards and I stitched eyelet holes at the back to allow for lacing-up. The original stays would have had metal rings to reinforce the eyelet holes which I had to do without as I could not find any of the right size. There was a line of boning between the eyelet holes and the centre back edge to give a neat finish |  |

I made the stays a few years ago and am still happy with their authenticity and their fit. The busk is remarkably comfortable and does stay in place.

Bibliography

A Visual History of Costume in the 17th Century

By Valerie Cumming

Pub Batsford

ISBN 0 7134 40937

The Cut of Women’s Clothes 1600 – 1930

By Norah Waugh

Pub Faber & Faber

ISBN 0571 085946

Corsets and Crinoline

By Norah Waugh

Pub Batsford

ISBN 0 7134 5699

Patterns of Fashion, The Cut and Construction of Clothes for Men and Women c. 1560 – 1620

By Janet Arnold

Pub Macmillian

ISBN 0333 382845